Have you ever looked at code reading/writing to a large or infrequently used datastructure and thought “What a waste of the cache?” Look no further than nontemporal memory operations for all your cache-bypassing needs.

Nontemporal memory access in Intel x86

Modern x86 chips1 contain load and store operations that completely bypass the cache, usually described as nontemporal memory operations. These instructions have some desireable properties for cache control, mainly:

- Will not allocate new lines in the cache, instead loading/storing directly to ram

- Are not ordered with regard to other loads/stores, giving the CPU more flexibility in hiding memory latency

Unfortunately, nontemporal loads only operate on memory mapped as write-combining, something not readily available in userspace. For now I’ll just focus on nontemporal stores and later talk about the module and ways to use nontemporal loads. We’ll get some basic benchmarks of how nontemporal stores interact with the cache and the normal store ordering system, and then try a small example showing how nontemporal stores can prevent cache pollution in practice.

Mechanics of nontemporal stores

While the Intel documentation is flush with details of how normal stores work, much less attention is given to the characteristics of nontemporal stores. As a result, most of the findings here are inferred from timing data. The full code is available in this repo.

Basic cache tests

Before embarking on any more advanced analysis, it’s useful to confirm that the nontemporal stores won’t write-allocate and therefore won’t pollute the cache. Our benchmark loop will be:

uint64_t run_timer_loop(void) {

shuffle_list();

mfence();

for (int i = 0; i < STORES_BEFORE; i++) {

force_store(&large_prestore_buffer[i]);

}

for (int i = 0; i < NT_STORES_BEFORE; i++) {

force_nontemporal_store(&large_prestore_buffer[i]);

}

mfence();

uint64_t start = rdtscp();

iterate_list();

uint64_t end = rdtscp();

}

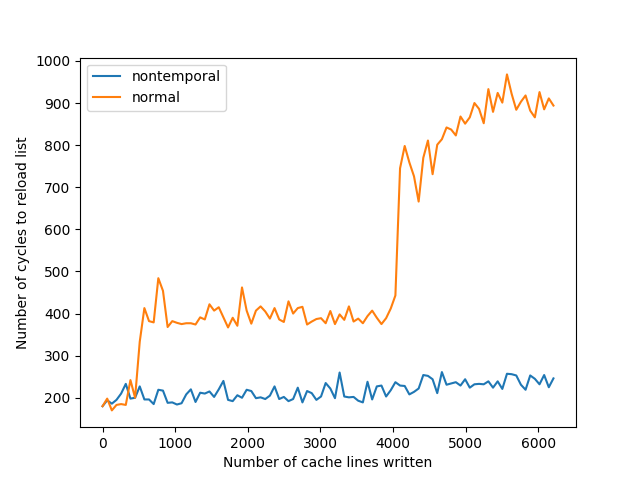

We’ll try writing between 0 and 6000 cache lines of either normal stores or nontemporal stores, and time iterating a shuffled linked list.2

The results are:

As one would expect, write allocation from normal stores evicts our list from the cache, but nontemporal stores don’t write-allocate and hence don’t evict our list. The results might seem obvious, but it’s worth confirming that there aren’t unexpected interactions between the cache system and nontemporal stores.

Interactions with normal stores

Nontemporal stores are documented as being unordered with respect to other stores as a performance optimization. How this plays out in practice is important since nontemporal stores have a huge, albeit usually unobserved latency. If in-flight nontemporal stores can occupy resources that would otherwise be used by normal operations, the processor would be unable to hide their latency.

To test this, we’ll execute a series of nontemporal stores before a series of normal stores and measure any interference or performance impact. The inner timing code we run will be:

uint64_t run_timer_loop(void) {

for (int i = 0; i < LINES; i++) {

force_load(&large_buffer[i]);

}

for (int i = 0; i < LINES; i++) {

clflush(&large_nontemporal_buffer[i]);

}

mfence();

uint64_t start = rdtscp();

for (int i = 0; i < NT_LINES; i++) {

force_nt_store(&large_nontemporal_buffer[i]);

}

for (int i = 0; i < NT_LINES; i++) {

force_store(&large_buffer[i]);

}

// while rdtscp 'waits' for all preceding instructions to complete,

// it does not wait for stores to complete as in be visible to

// all other cores or the L3, but for the instruction to be retired

// this makes it easy to benchmark the visible effects of

// nontemporal stores on normal stores and look for stalls

uint64_t end = rdtscp();

}

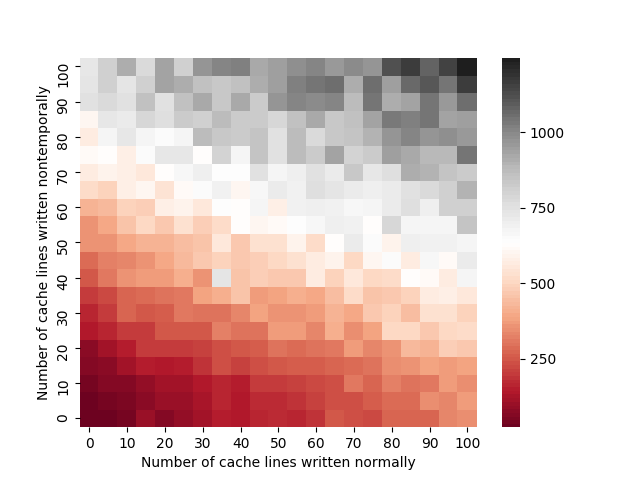

We can run a test trying each combination of NT_LINES and LINES from 0 to 100, at increments of 5 each.3 The results are:

The results confirm what one would expect:

- Since nontemporal stores are unordered with respect to other stores, they don’t prevent normal stores from completing

- The costs scale approximately linearly with the number of stores in either dimension, and there’s no performance wall or major stall

- Nontemporal stores have some slight throughput penalty over normal store operations

Importantly, there doesn’t seem to be any additional cost to subsequent stores after a series of nontemporal stores is executed. Contrast this with the case where

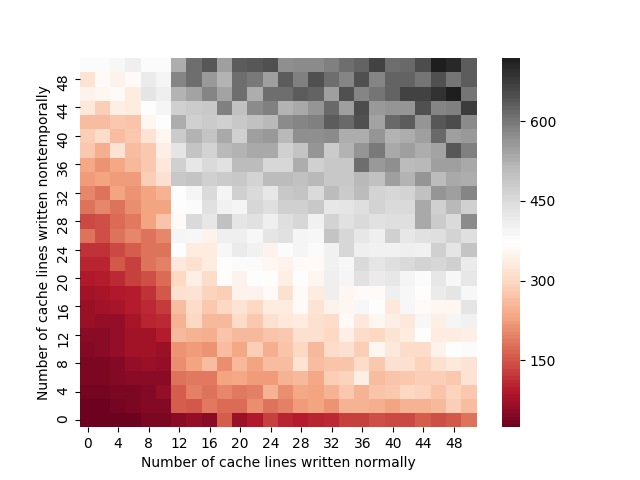

we execute an sfence instruction4 between the nontemporal and normal stores:

This won’t be relevant except when writing multicore code, but the previous benchmark is a great example of what happens when nontemporal stores block normal stores. Eventually, normal stores can’t issue any more since the store buffer fills up and the processor just stalls.

Write combining buffers

Write combining buffers exist on the CPU to help coalesce stores into a single operation. On normal stores, this allows reads-for-ownership to coalesce for consecutive stores to the cache line, but otherwise is not fundamental to performance. For nontemporal stores, they play a much more fundamental role.5

Since the memory bus on Intel processors will break up transactions smaller than 64 bytes into many smaller transactions, write combining buffers allow a set of nontemporal stores to the same line to accumulate until the entire line is written. There’s a limited number of these buffers, so one must ensure that whole cache lines are written at once with nontemporal stores.6 We can get some basic idea of how bad this is with the following benchmark:

We’ll run this code in the inner loop:

void force_nt_store(cache_line *a) {

__m128i zeros = {0, 0}; // chosen to use zeroing idiom;

__asm volatile("movntdq %0, (%1)\n\t"

#if BYTES > 16

"movntdq %0, 16(%1)\n\t"

#endif

#if BYTES > 32

"movntdq %0, 32(%1)\n\t"

#endif

#if BYTES > 48

"movntdq %0, 48(%1)"

#endif

:

: "x" (zeros), "r" (&a->vec_val)

: "memory");

}

uint64_t run_timer_loop(void) {

mfence();

uint64_t start = rdtscp();

for (int i = 0; i < 32; i++) {

force_nt_store(&large_buffer[i]);

}

mfence();

uint64_t end = rdtscp();

}

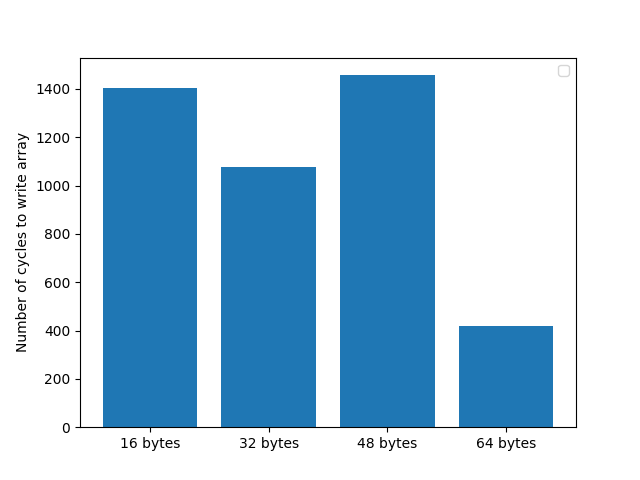

We initiate a series of nontemporal stores and issue a strong fence to time how long they take to complete.

As expected, writing partial cache lines seriously hurts performance:

Downsides and performance traps

Using nontemporal stores requires a lot of caution and knowledge about the memory access characteristics of your software. Nontemporal stores will evict lines from the cache if present, effectively causing the same thing you would be trying to prevent. Further, nontemporal stores do not forward to loads - any loads to addresses with a nontemporal store in flight will simply stall until the store is complete, and then load from ram. Finally, subtle characteristics of these instructions are different across processors, meaning you have to run benchmarks on all hadware you use.

These instructions should only be used with care and benchmarking+profiling of an application beforehand. You’re explicitely bypassing the single most important modern hardware optimization. Make sure that you consistently have a cache problem, and that nontemporal stores can help it, before having your software use them.

What can we do with just this?

Unfortunately, there’s not a whole lot that we can do with just stores on a single thread. Nontemporal stores could be useful for writing to low-priority threads on a different socket, but ordering via fences and the performance implications of the required fences are tricky enough to deserve their own article. For the sake of this article, I’ll write a fairly contrived example; however, the interesting applications don’t arise until we can access nontemporal loads and have a good multicore story.

Consider this situation: You have some function which receives a long message containing a user ID, looks up that user in some datastructure, and forwards the result on to some different processing pipeline. Furthermore, you must keep the last N received messages in a buffer to log upon a rare failure case, enough messages such that writing them pollutes your cache. We’ll benchmark this scenario and see how nontemporal stores reduce the cache pressure of this buffer and keep the lookup datastructure in cache. The basic outline of our test code will be:

struct message {

uint64_t id;

char data[1024*8 - sizeof(uint64_t)];

};

std::map<uint64_t, uint64_t> lookup_map;

std::vector<message> message_buffer;

size_t message_buffer_ind;

void process_message(const message &m) {

message &cpy_to = message_buffer[message_buffer_ind];

message_buffer_ind++;

if (message_buffer_ind == message_buffer.size()) {

message_buffer_ind = 0;

}

#ifdef NONTEMPORAL_COPY

nontemporal_cpy_message(m, cpy_to);

#else

// One can experiment with prefetching here to avoid

// problems with RFO on normal stores hitting RAM,

// but empirically the CPU prefetcher does a fine job of that already

cpy_message(m, cpy_to);

#endif

process_message_more(m, lookup_map[m.id]);

}

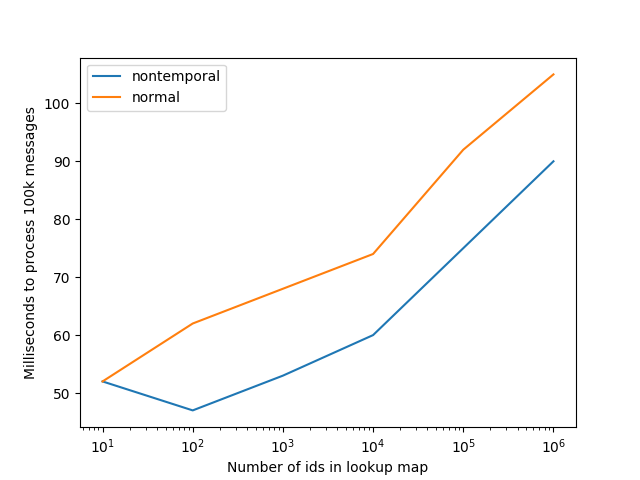

We’ll adjust the number of IDs in the map (and in the message) and see how each performs. If we store 50MB of

old messages, the results are:

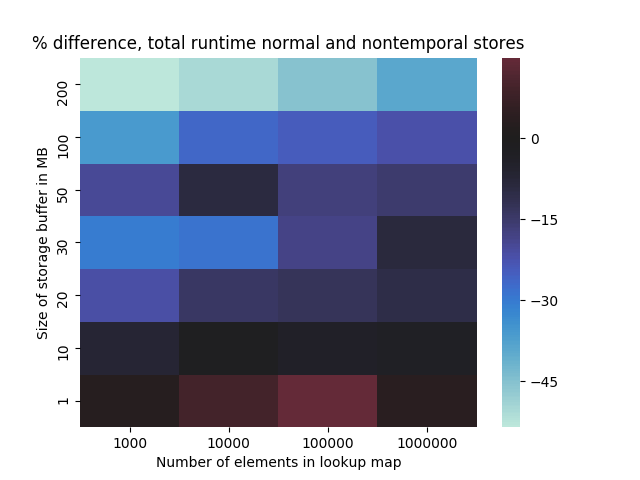

We can plot the performance difference between the normal and nontemporal stores for varying buffer sizes as well:

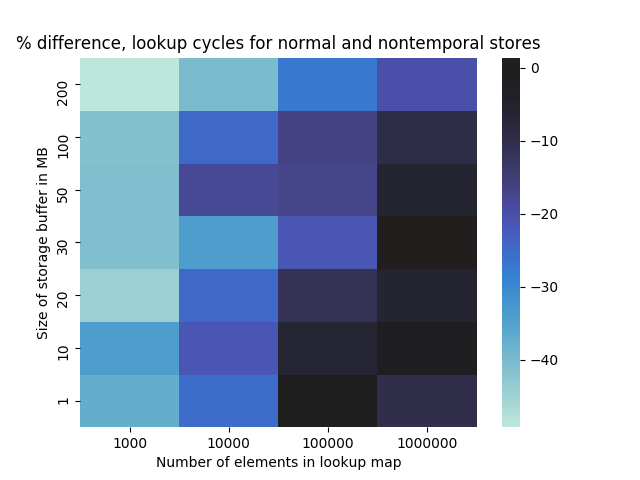

And as a sanity check, the same heatmap but for the average number of cycles spent in the lookup table:

As we make the message buffer larger, nontemporal operations reduce cache pressure in the tree lookup and we see a performance improvement. Larger trees tend to show less improvement as the tree itself does not fit in the cache and the benchmark does not perform enough iterations to load the whole tree. Although this is essentially a re-demonstration of the simple write allocation test done earlier, it is useful to confirm in a psuedo-real application. Hopefully, this was sufficient to demonstrate that nontemporal operations, even just stores, have a meaningful use in high performance applications.7 With later posts we’ll see how useful nontemporal operations are when we can load past the cache as well.

1. Nontemporal stores were introduced in SSE, and loads in SSE 4.1↩

2. Iterating a list help reduce variability by having to hit multiple lines in a prefetcher-invisible way↩

3. There are a huge set of variations of this to test - nontemporal store for lines in L1? L2? L3? Normal stores to lines out of cache? I don’t want to spam this with minor variations of the same benchmark↩

4. sfence enforces ordering between stores, but is weaker than mfence in that it doesn’t enfore store-load ordering. In practice this means it has no effect on normal stores, and prevents normal stores from leaving the store buffer as long as a nontemporal store is still in flight↩

5. This is an extremly simplified discussion of write combining buffers, and confusingly different than write combining memory↩

6. I haven’t run benchmarks on what constitutes a block, but almost all sensible cases will be in a memcpy-like setting where the stores are issued as fast as possible↩

7. One should run all the tests from the repo, since results can vary based on the hardware even within a product line↩